Study Shows BMI Affects Brain Connectivity in Men and Women Differently

Obesity is an increasingly recognized and studied modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). But what is less known is if a higher body mass index (BMI) affects men’s and women’s brains differently.

A team of researchers from Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis published a study showing that brain connectivity appears to decline for men at a lower weight than women. While men’s brain connectivity showed detrimental effects in the overweight (BMI of 25 –29.9) to obese (BMI of 30 or more) categories, women’s brain connectivity didn’t decline until the obese range.

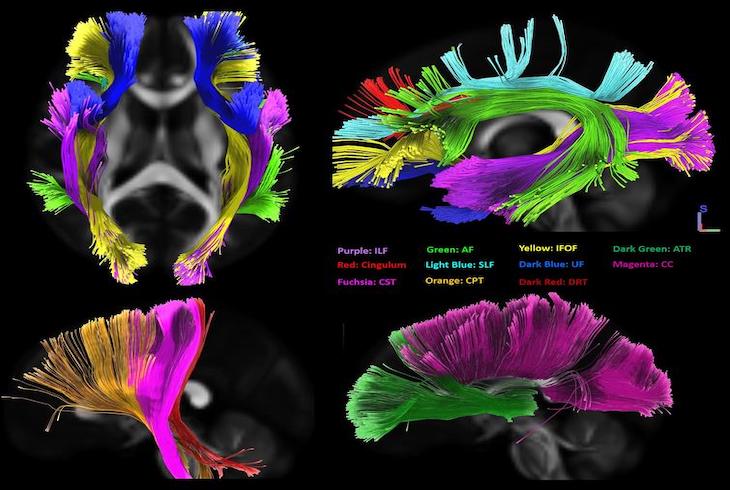

The study, published Feb. 17 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, specifically studied how BMI affected white matter connectivity in the brain. While gray matter — or the neurons of the central nervous system — is more commonly studied in AD research, there is less known about white matter, which controls connection and communication between those neurons.

“The white matter is kind of like your cable internet connection in the brain,” said senior author Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of radiology in MIR’s Neuroimaging Labs Research Center. “If you don’t have that connectivity, you’re not going to be able to transmit information and wire neurons together as effectively. Having that understanding is new because traditionally we’ve studied neurons, but not the connection between them.”

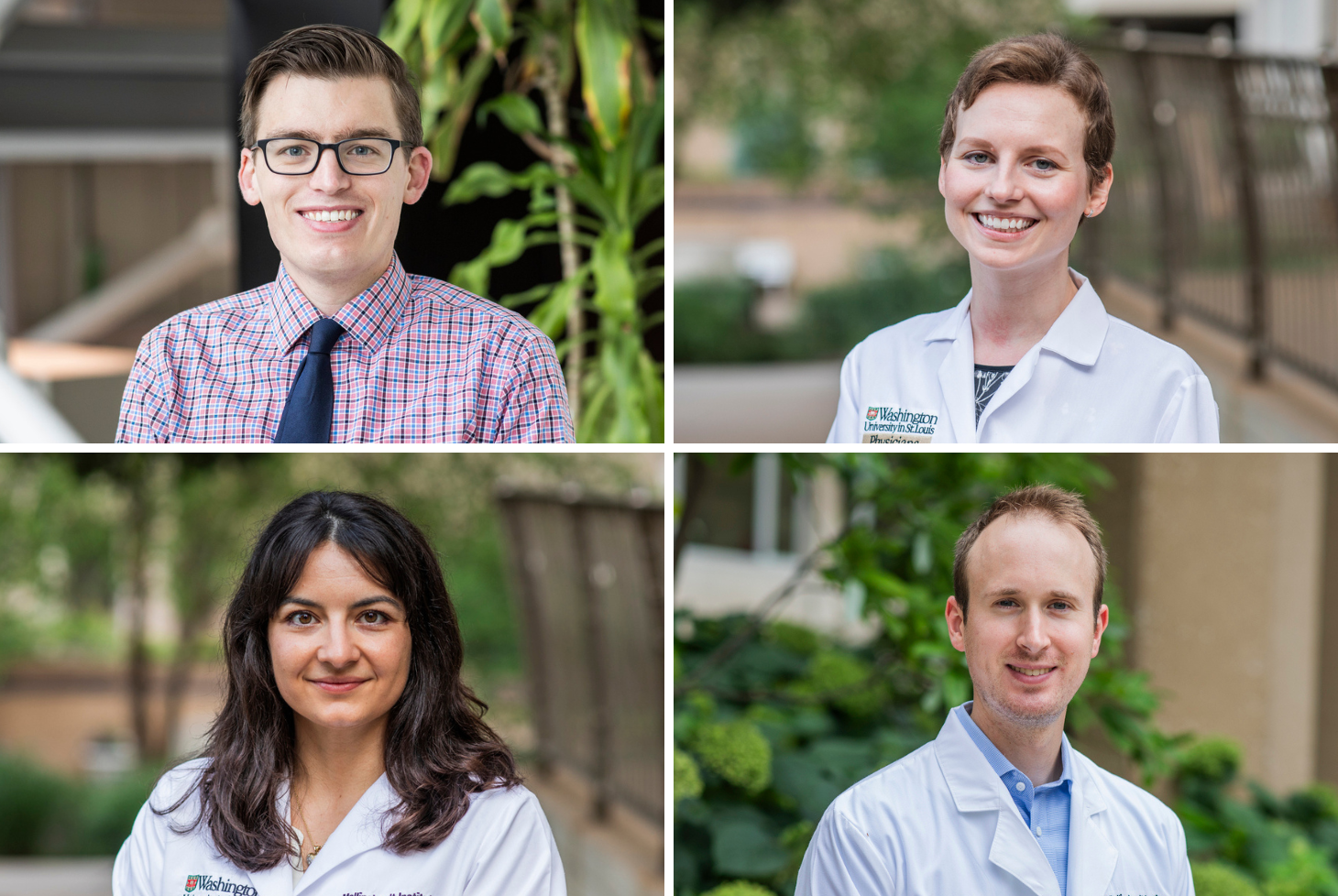

Raji along with first author Farzaneh Rahmani, MD, a postdoctoral research associate, and colleagues at MIR and in the Department of Neurology studied 231 cognitively normal participants from the university’s Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center. The participant cohort consisted of 107 men and 124 women between the ages of 42 and 88 years old.

From preventing alcohol misuse to improving access to education, research shows that up to 40% of dementia cases can be prevented by a series of modifiable risk factors. With that knowledge, researchers like Raji and Rahmani are seeking to learn the relationship that biological sex differences might have with these risk factors, which could help optimize AD prevention strategies. “There is an increasing interest by the National Institutes of Health to understand sex as a biological variable in Alzheimer’s disease, making our study’s focus both simple and important,” said Rahmani.

While the study provides insight into the relationship between BMI, biological sex and AD, it also illuminates the potential in studying other AD modifiable risk factors and expanding research to more populations so the science can better inform public health and policy.

“This study provides a target for future studies to investigate the effect of lifestyle modifications to combat adolescent and adulthood obesity in reducing life-long risk of dementia,” Raji said.

Read the full study in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. The study will be published in the print edition of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Volume (86) Volume (4).

This research was supported by the following grants: KL2 TR000450–ICTS Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Program from Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis, as well as the National Institutes of Health 1RF1AG072637-01 (CAR), P30AG066444 (JCM), R01AG054567-01A1 (TLSB), P01AG026276 (JCM), P01AG003991 (JCM), and support for image acquisition and informatics through UL1TR000448, P30NS098577, and EB009352.

SES is supported by K23AG053426. Additional support was provided by the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center Support Fund and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation, and the Radiological Society of North America Research Scholar Grant.

Authors’ disclosures available online.