“For all patients with lung cancer, the average five-year survival rate is around 25%,” said David S. Gierada, MD, professor of radiology at Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR). Gierada works closely with the Lung Cancer Screening Program at Siteman Cancer Center. “For patients with advanced-stage cancer, that percentage drops to about 5%. But when patients are diagnosed while in stage 1, their five-year survival rate is 65% and above. These statistics make our goal obvious: detect lung cancer at its earliest stage so that patients have their best chance of undergoing successful treatment.”

A Breakthrough in Screening

Research focused on detecting early-stage lung cancer dates to the 1970s, when studies were conducted to test the efficacy of chest X-ray combined with sputum cytology. None of the trials proved to reduce deaths from lung cancer.

The breakthrough in lung cancer screening came when researchers began considering the use of computed tomography (CT) scans as a means of detecting the disease. “It was long known that CT could identify smaller lung nodules than those seen on chest X-rays, but it came with a significantly higher dose of radiation, as well as with a considerably higher cost,” said Gierada. “Then in the mid-to-late 1990s, researchers began investigating the use of low-dose CT as a more acceptable way to find lung cancer early in persons at high risk due to their smoking history and age.”

The promising results of these initial studies led to several impactful studies including the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The eight-year, randomized-control trial, launched in 2002, enrolled more than 50,000 current or former heavy smokers between the ages of 55–74, who were divided into an X-ray group and a low-dose CT group. Participants committed to receiving annual screenings for three years.

According to the NCI, the results comparing the two imaging methods were clear: lung cancer deaths in the CT group were 20% lower than those in the X-ray group. The positive and encouraging findings resulted in an earlier end to the study than originally planned.

“A subsequent large study in Europe similarly found fewer lung cancer deaths in those screened with low-dose CT,” said Gierada, who served as lead radiology investigator for the NLST site at WashU Medicine. “In 2014, low-dose CT screening for lung cancer became the recommended clinical practice, and it serves as the foundation for the Siteman Lung Cancer Screening Program.”

Screening Early and Improving Patient Outcomes

The Siteman Lung Cancer Screening Program offers screenings at seven sites: Washington University Medical Campus, Center for Advanced Medicine – South County, Barnes-Jewish West County Hospital, Christian Hospital, Northwest HealthCare, Barnes-Jewish St. Peters Hospital and Progress West Hospital. Since its start in 2016, the program has diagnosed 291 cases of lung cancer. And a 2021 update to national screening guidelines — including lowering the minimum screening age — enabled more high-risk people to get screened.

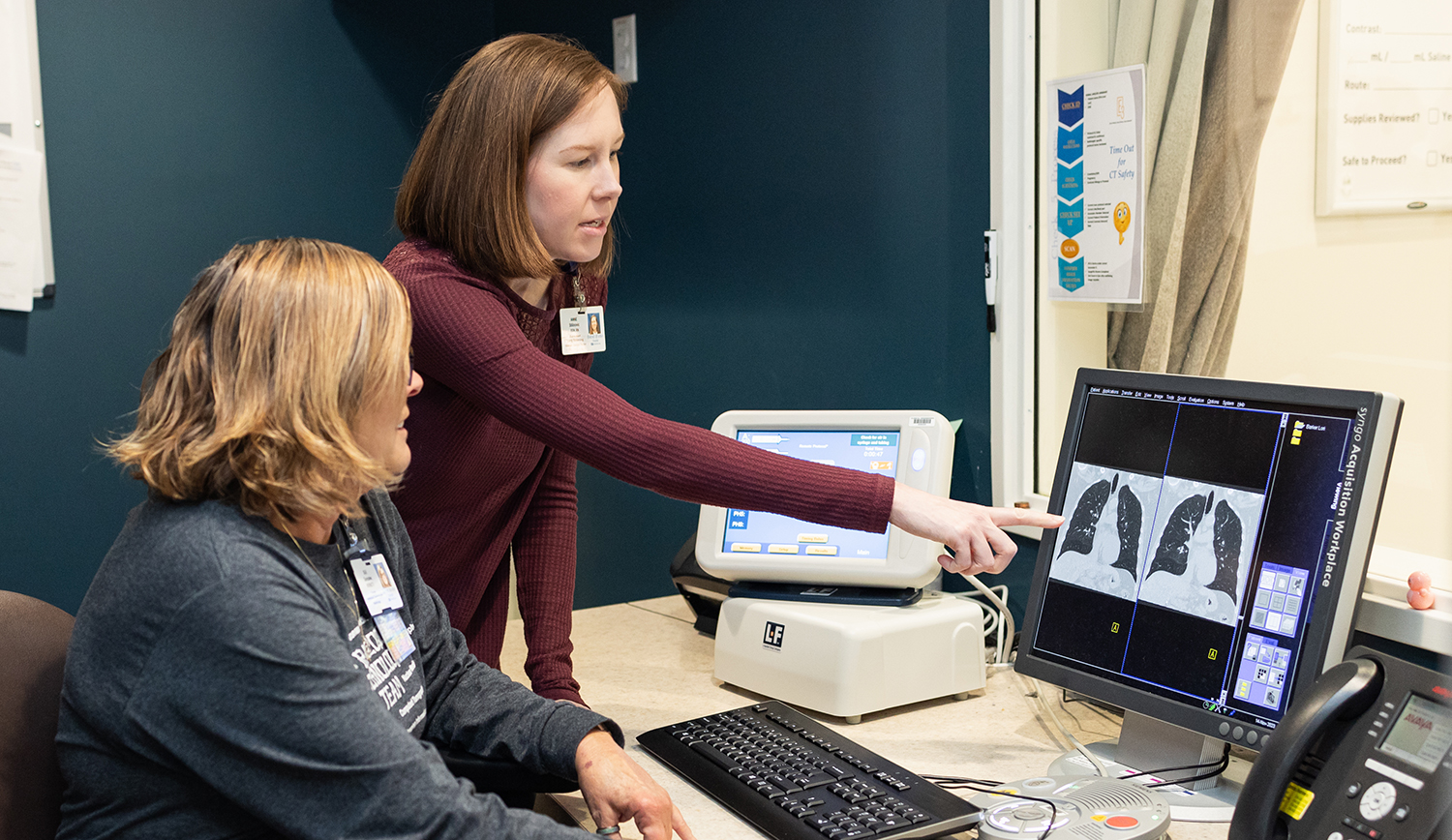

“Of the 291 cases, 71% were early stage, which is exactly the point of screening,” said Anne Stilinovic, RN, supervisor of the screening program. “To be most effective, screenings should be done annually for at least three years, but ideally for every year a person is eligible to have one. The screening is noninvasive, doesn’t require any type of special preparation and takes just a few minutes.”

CT scans at all screening locations are evaluated by MIR radiologists within 24 hours. A nurse navigator mails negative results to patients and their physicians; if a nodule or advanced cancer is found, patients and their physicians are called immediately. From that point, the navigators act as intermediaries to facilitate communication between patients and the physicians involved in their care. A follow-up plan can range from “watchful waiting” — scheduling additional scans in three to six months when relatively small nodules show potential for being a lung cancer — to discussions about surgery or other advanced treatment.

The recommendation for annual screenings stems from the CT technology’s capacity for detecting lung nodules as small as 1-2 millimeters and clinical trial data showing that new nodules on annual screening are more likely to be malignant than nodules present on the initial screening. “When nodules are small, we are unable to determine whether they are cancerous. Consecutive scans allow us to note any changes that may occur,” said Gierada. “This helps to avoid overtreatment of the small nodules that are benign, which is most of them, while still catching those that are malignant far earlier and when they are more treatable than if they weren’t found until they caused symptoms.”

Patient Randy Blanc’s experience illustrates the worth of annual lung screenings. Blanc, 70, began smoking at age 20 and at one point smoked a pack to a pack-and-a-half a day. Over the past dozen years, he has cut back to two to four cigarettes daily. At the recommendation of his physician, three years ago Blanc had his first lung cancer screening at Barnes-Jewish West County Hospital. A small nodule was detected.

“My follow-up scans have shown there’s been no change in the nodule, and that’s been good news each year,” said Blanc. “The screening is such a quick and easy procedure. I’d recommend it to anyone who is or was a heavy smoker to see if the health of their lungs has been affected.”

About 15 of every 100 patients screened for the first time have a nodule requiring further evaluation. Although these can cause worry, most people simply need another scan to determine if what was detected is stable or if it changes. Because the CT scan begins at the base of the neck and ends at the upper abdomen, it also may show incidental findings, such as problems with the thyroid or coronary artery disease, that could need follow-up evaluation.

Breaking Down Barriers

In addition to the specific eligibility requirements (see inset box), unlike screenings for breast and colon cancers, an order from a provider is required. “Whether or not a lung cancer screening is appropriate for patients is a shared decision between themselves and their health-care providers,” said Gierada. “For instance, the conversation should inform patients of the potential benefits of lung cancer screening, describe the risks associated with the procedure, and ensure patients’ values and preferences are taken into consideration.”

Despite the proven effectiveness of lung cancer screening, only about 5% of those eligible in the U.S. are screened per year. Several barriers exist that contribute to this low percentage. Some patients are unable to get an order for a screening because they don’t have a doctor, or they don’t have insurance and can’t afford to pay for the screening. Others may be in denial of the risks associated with smoking. And providers may not be familiar with nodule management guidelines or aware of the positive outcomes associated with the use of low-dose CT scans for lung cancer screening.

Although some barriers require systemic changes to health-care availability, there are efforts to improve communication within the health-care community. For example, WashU Medicine researchers at Siteman participated in I-STEP (Increasing Screening Through Engaging Primary Care Providers), a clinical trial with the goal of improving primary care physicians’ awareness of the benefits of lung cancer screening.

Quitting: A Judgment-Free, Holistic Approach

The Siteman Lung Cancer Screening Program provides various resources to patients, including contact information for a Tobacco Quitline, an Online Quit Plan and the American Cancer Society Quit for Life Program. A point-of-care tobacco treatment program developed by university researchers offers strategies such as free, text-based counseling; recommendations for free phone apps to NCI smoking cessation platforms; FDA-approved medications to stop or reduce smoking; and referrals to a free smoking cessation program.

“In addition, Siteman psychologists recently developed a virtual smoking cessation course called the Tobacco Use Treatment Program. It offers participants the flexibility of meeting remotely once a week for four weeks,” said Stilinovic. “And an in-person smoking cessation group is under development by our nurse navigator at Christian Hospital.”

Gierada said research into alternative methods of lung cancer screening that may complement CT screening, particularly blood biomarkers, are ongoing. But for now, “Screening with low-dose CT scans is effective, safe and convenient. And it is saving lives.”

Lung Screening Eligibility Requirements

Medicare, Medicaid and most private insurance companies cover the cost of annual lung cancer screenings, but there are specific eligibility requirements:

• Patients must be age 50-80 years old (Medicare covers age 50-77).

• They must have smoked at least one pack a day for 20 years, 3/4 pack for 30 years, or 1/2 pack for 40 years.

• They are current smokers or quit within the past 15 years.

Published in Focal Spot Winter 2024 Issue